George Muller

George Müller (German - born as : Johann Georg Ferdinand Müller) (September 27, 1805 – March 10, 1898), a Christian evangelist and Director of orphanages in Bristol, England, cared for 10,024[1] orphans in his life[2] He was well-known for providing an education to the children under his care, to the point where he was accused of raising the poor above their natural station in life. He also established 117 schools which offered Christian education to over 120,000 children, many of them being orphans.

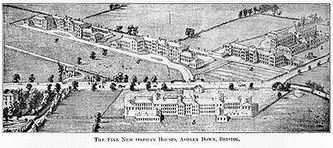

The work of Müller and his wife with orphans began in 1836 with the preparation of their own home at 6 Wilson Street, Bristol for the accommodation of thirty girls. Soon after, three more houses in Wilson Street were furnished, growing the total of children cared for to 130. In 1845, as growth continued, Müller decided that a separate building designed to house 300 children was necessary, and in 1849, at Ashley Down, Bristol, that home opened. The architect commissioned to draw up the plans asked if he might do so gratuitously[12]. By 26 May 1870, 1,722 children were being accommodated in five homes, although there was room for 2,050 (No 1 House - 300, No 2 House - 400, Nos 3, 4 and 5 - 450 each). By the following year, there were 280 orphans in No 1 House, 356 in No 2, 450 in Nos 3 and 4, and 309 in No 5 House[13].

Through all this, Müller never made requests for financial support, nor did he go into debt, even though the five homes cost over £100,000 to build. Many times, he received unsolicited food donations only hours before they were needed to feed the children, further strengthening his faith in God. For example, on one well-documented occasion, they gave thanks for breakfast when all the children were sitting at the table, even though there was nothing to eat in the house. As they finished praying, the baker knocked on the door with sufficient fresh bread to feed everyone[14].

Although he never asked any person (other than God) for anything, Müller asked those who did support his work to give a name and address in order that a receipt might be given. The receipts were printed with a request that the receipt be kept until the next annual report was issued, in order that the donor might confirm the amount reported with the amount given. Every single gift was recorded, whether a single farthing, £3,000 or an old teaspoon. Accounting records were scrupulously kept and made available for scrutiny[15].

Every morning after breakfast there was a time of Bible reading and prayer, and every child was given a Bible upon leaving the orphanage, together with a tin trunk containing two changes of clothing. The children were dressed well and educated - Müller even employed a schools inspector to maintain high standards. In fact, many claimed that nearby factories and mines were unable to obtain enough workers because of his efforts in securing apprenticeships, professional training, and domestic service positions for the children old enough to leave the orphanage[16]. In 1871 an article in The Times stated that since 1836, 23,000 children had been educated in the schools and very many thousands had been educated in other schools at the expense of the orphanage. The article also states that since its origin, 64,000 Bibles, 85,000 Testaments and 29,000,000 religious books had been issued and distributed. Other expenses included the support of 150 missionaries.[17]

The author, Charles Dickens, heard a rumor[18] that the orphans were being mistreated and came down from London unannounced to verify this. Initially, Müller refused to grant access as it was not one of the days set aside to receive visitors to the homes, but Dickens refused to leave. It is unclear whether Müller showed Dickens around himself, or if he gave Dickens a bunch of keys and invited him to go around the homes, or if he tasked one of the orphans to guide Dickens round, but Dickens went back to London and wrote a fulsome report on the activities of the orphan houses in his publication "Household Words" [19]. Strangely, Müller makes no mention of this visit in his writings.

References

Notes

1. Autobiography of George Müller page 693

2. Pierson, Arthur (1899). George Müller of Bristol. London: James Nisbet & Co., Limited., Page 301.

12."Delighted in God", Roger Steer, ISBN 1-85792-340-5, page 98-101

13.The Narratives and Addresses Vol 1 ISBN 0-9705439-6-4 page354

14."Delighted in God", Roger Steer, ISBN 1-85792-340-5, page 131

15. The Narratives and Addresses Vol 1 ISBN 0-9705439-6-4 and Annual Reports 1834 - present

16."Delighted in God", Roger Steer, ISBN 1-85792-340-5, page 140, 152-3

17.The Times, Monday, December 11th, 1871

18. "My Book of Remembrance", by Charles Brewer October 1909 (copy held at The George Müller Charitable Trust)

19. Household Words edition 398, published Saturday 7 November 1857

The above article was excerpted from Wikipedia. To read the entire article click on the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_M%c3%bcller

The work of Müller and his wife with orphans began in 1836 with the preparation of their own home at 6 Wilson Street, Bristol for the accommodation of thirty girls. Soon after, three more houses in Wilson Street were furnished, growing the total of children cared for to 130. In 1845, as growth continued, Müller decided that a separate building designed to house 300 children was necessary, and in 1849, at Ashley Down, Bristol, that home opened. The architect commissioned to draw up the plans asked if he might do so gratuitously[12]. By 26 May 1870, 1,722 children were being accommodated in five homes, although there was room for 2,050 (No 1 House - 300, No 2 House - 400, Nos 3, 4 and 5 - 450 each). By the following year, there were 280 orphans in No 1 House, 356 in No 2, 450 in Nos 3 and 4, and 309 in No 5 House[13].

Through all this, Müller never made requests for financial support, nor did he go into debt, even though the five homes cost over £100,000 to build. Many times, he received unsolicited food donations only hours before they were needed to feed the children, further strengthening his faith in God. For example, on one well-documented occasion, they gave thanks for breakfast when all the children were sitting at the table, even though there was nothing to eat in the house. As they finished praying, the baker knocked on the door with sufficient fresh bread to feed everyone[14].

Although he never asked any person (other than God) for anything, Müller asked those who did support his work to give a name and address in order that a receipt might be given. The receipts were printed with a request that the receipt be kept until the next annual report was issued, in order that the donor might confirm the amount reported with the amount given. Every single gift was recorded, whether a single farthing, £3,000 or an old teaspoon. Accounting records were scrupulously kept and made available for scrutiny[15].

Every morning after breakfast there was a time of Bible reading and prayer, and every child was given a Bible upon leaving the orphanage, together with a tin trunk containing two changes of clothing. The children were dressed well and educated - Müller even employed a schools inspector to maintain high standards. In fact, many claimed that nearby factories and mines were unable to obtain enough workers because of his efforts in securing apprenticeships, professional training, and domestic service positions for the children old enough to leave the orphanage[16]. In 1871 an article in The Times stated that since 1836, 23,000 children had been educated in the schools and very many thousands had been educated in other schools at the expense of the orphanage. The article also states that since its origin, 64,000 Bibles, 85,000 Testaments and 29,000,000 religious books had been issued and distributed. Other expenses included the support of 150 missionaries.[17]

The author, Charles Dickens, heard a rumor[18] that the orphans were being mistreated and came down from London unannounced to verify this. Initially, Müller refused to grant access as it was not one of the days set aside to receive visitors to the homes, but Dickens refused to leave. It is unclear whether Müller showed Dickens around himself, or if he gave Dickens a bunch of keys and invited him to go around the homes, or if he tasked one of the orphans to guide Dickens round, but Dickens went back to London and wrote a fulsome report on the activities of the orphan houses in his publication "Household Words" [19]. Strangely, Müller makes no mention of this visit in his writings.

References

- Müller, George. Autobiography of George Müller. ISBN 0964755203.

- George Muller by James J Ellis, published by Pickering & Inglis.

- "Müller, George." Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals. Timothy Larsen, editor. Downers-Grove, Illinois: Intevarsity Press, 2003.

- "Müller, George." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

- Pierson, A. T. George Müller of Bristol. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications, 2000.

Notes

1. Autobiography of George Müller page 693

2. Pierson, Arthur (1899). George Müller of Bristol. London: James Nisbet & Co., Limited., Page 301.

12."Delighted in God", Roger Steer, ISBN 1-85792-340-5, page 98-101

13.The Narratives and Addresses Vol 1 ISBN 0-9705439-6-4 page354

14."Delighted in God", Roger Steer, ISBN 1-85792-340-5, page 131

15. The Narratives and Addresses Vol 1 ISBN 0-9705439-6-4 and Annual Reports 1834 - present

16."Delighted in God", Roger Steer, ISBN 1-85792-340-5, page 140, 152-3

17.The Times, Monday, December 11th, 1871

18. "My Book of Remembrance", by Charles Brewer October 1909 (copy held at The George Müller Charitable Trust)

19. Household Words edition 398, published Saturday 7 November 1857

The above article was excerpted from Wikipedia. To read the entire article click on the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_M%c3%bcller